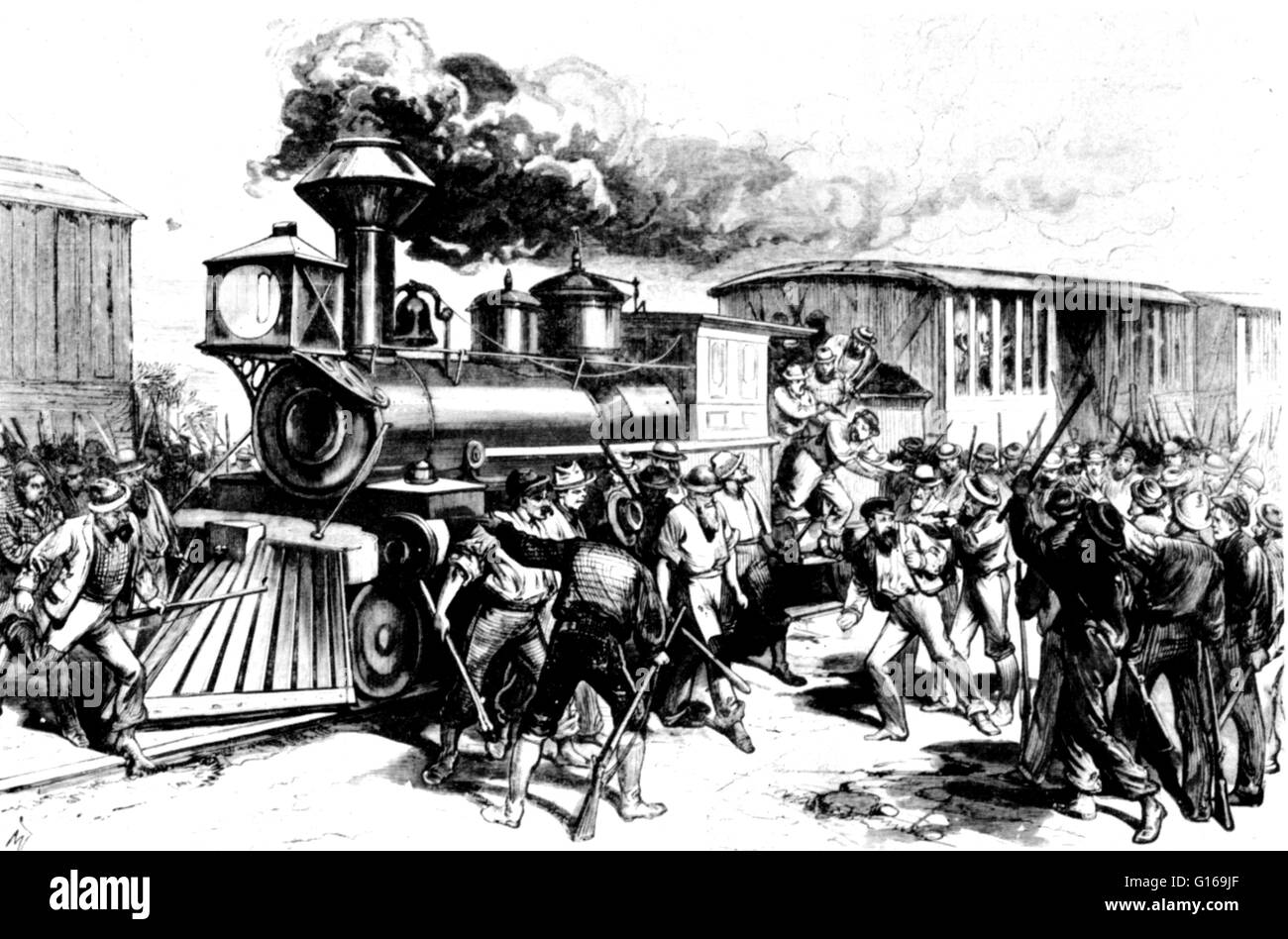

By the early 1880s, even farmers began to fully recognize the strength of unity behind a common cause.īusiness owners generally viewed organization efforts with great mistrust, capitalizing upon widespread anti-union sentiment among the general public to crush unions through a variety of tactics. But, as economic conditions changed, people became more aware of the inequities facing factory wage workers. With the majority of workers in the country working independently in rural settings, the idea of organized labor was not largely understood. Prior to the Civil War, there were limited efforts to create an organized labor movement on any large scale. Worker Organization and the Struggles of Unions It convinced laborers of the need for institutionalized unions, persuaded businesses of the need for even greater political influence and government aid, and foretold a half-century of labor conflict in the United States. Nearly 100 Americans died in what came to be known as “The Great Upheaval.” Workers destroyed nearly $40 million worth of property. Six weeks after it had begun, the strike had been crushed. Soldiers moved from town to town, suppressing protests and reopening rail lines. Hayes, American soldiers were deployed all across northern rail lines. When militia in West Virginia refused to break the strike, federal troops broke it instead. When Pennsylvania militiamen were unable to contain the strikes, federal troops stepped in. Rail lines were shut down all across neighboring Illinois, where coal miners struck in sympathy, tens of thousands gathered to protest under the aegis of the Workingmen’s Party, and twenty protesters were killed in Chicago by special police and militiamen.Ĭourts, police, and state militias suppressed the strikes, but it was federal troops that finally defeated them. Federal troops and vigilantes fought their way into the depot, killing eighteen and breaking the strike.

Louis, and strikers seized rail depots and declared for the eight-hour day and the abolition of child labor. The militia fired into the crowd, killing ten people. In Reading, strikers destroyed rail property and an angry crowd bombarded militiamen with rocks and bottles. Strikers set fire to the city, destroying dozens of buildings, over one hundred engines, and over a thousand railcars.

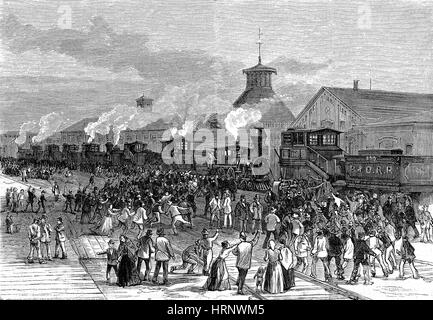

The head of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Thomas Andrew Scott, suggested that if workers were unhappy with their wages, they should be given “a rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread.” Law enforcement in Pittsburgh refused to put down the protests, so the governor called out the state militia, who killed twenty strikers with bayonets and rifle fire. Strikes convulsed towns and cities across Pennsylvania. In Baltimore, the militia fired into a crowd of striking workers, killing eleven and wounding many more. The governor of Maryland deployed the state’s militia. Many strikers destroyed rail property rather than allow militias to reopen the rails. When local police forces would not or could not suppress the strikes, governors called out state militias to break them and restore rail service. Panicked business leaders and friendly political officials reacted quickly. Leiser in Harper’s Weekly, Journal of Civilization,” Vol XXL, No. Figure 1. “Destruction of the Union Depot,” Pittsburgh, PA, during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)